It is a war out there, and the front line combatants are women.

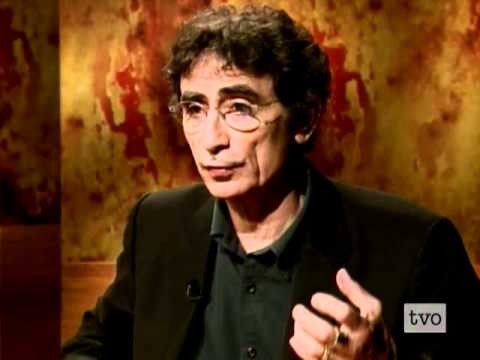

Dr Gabor Maté has charted the battles that rage within and without, which begin from the moment a zygote starts its journey of cell proliferation and eventually, attempts to survive as a creature facing a hostile environment.

Human infants are extraordinarily fragile and vulnerable mammal babies. Even when the fetus is ejected from the uterus at 40 weeks of gestation, there are still months and months of neuronal growth ahead.

This is when human beings are initiated to love, to acceptance, to nurturing, to the ways we make reason from chaos.

It is also when first we experience (and not vicariously through the hormones that flow through the umbilical cord) fear, anger, pain. Our bodies hold the wounds of battle suffered in the encounters between good-enough and inadequate nurturing. One would hope that all infants might be born into an environment that can foster optimum cerebral cortex development but that is not always so.

Dr Maté worked for years as a primary and family health care physician. He has tended to the physical and emotional needs of patients. He is a medical scientist who has observed, analyzed and researched the biochemical effect of early childhood traumatic events, the development of compensating mechanisms, the impact of stress upon brain function, and the development of disease within this framework.

He has concluded, based on his decades of work with individuals who cope as best they can given experiences of deprivation, loss, abandonment, neglect, emotional abuse and physical injuries during their childhood, that survival strategies are complex and potentially harmful.

From ‘When the Body Says NO: exploring the stress-disease connection’ (pp 33-36):

The stress response is non-specific. It may be triggered in reaction to any attack – physical, biological, chemical or psychological – or in response to any perception of attack or threat, conscious or unconscious. The essence of threat is a destabilization of the body’s homeostasis, the relatively narrow range of physiological conditions within which the organism can survive and function. To facilitate fight or escape, blood needs to be diverted from the internal organs to the muscles, and the heart needs to pump faster. The brain needs to focus on the threat, forgetting about hunger or sexual drive. Stored energy supplies need to be mobilized, in the form of sugar molecules. The immune cells must be activated. Adrenaline, cortisol and the other stress substances fullfill those tasks.

All these functions must be kept within safe limits: too much sugar in the blood will cause coma; an overactive immune system will soon produce chemicals that are toxic. Thus, the stress response may be understood not only as the body’s reaction to stress but also as its attempt to maintain homeostasis in the face of threat. […]

The oft-observed relationship between stress, impaired immunity and illness has given rise to the concept of the “diseases of adaptation” a phrase of Hans Selye’s. […]

The fight-or-flight alarm reaction exists today for the same purpose evolution originally assigned to it: to enable us to survive. What has happened is that we have lost touch with the gut feelings designed to be our warning system. The body mounts a stress response but the mind is unaware of the threat. We keep ourselves in physiologically stressful situations, with only a dim awareness of distress or no awareness at all. As Selye pointed out, the salient stressors in the lives of most human beings today – at least in the industrialized world – are emotional. Just like laboratory animals unable to escape, people find themselves trapped in lifestyles and patterns inimical to their health. The higher the level of economic development, it seems, the more anaesthetized we have become to our emotional realities. We no longer sense what is happening in our bodies and cannot therefore act in self-preserving ways. The physiology of stress eats away at our bodies not because it has outlived its usefulness but because we may no longer have the competence to recognize its signals.

Dr Maté has also lent his medical expertise, and cared for women using Insite and other community resources in Vancouver’s downtown eastside.

From a recent article about the Missing Women inquiry:

[Jamie Lee] Hamilton testified that the displacement of the sex trade from Vancouver’s West End to darker industrial areas of the city made it more dangerous for women working the streets.

The women were pushed out of the West End during a “Shame the Johns” campaign, which resulted in an injunction to stop prostitution in the area. […]

She also recalled women worked in clusters, to look out for each other, but police later discouraged clustering, which made things more dangerous and the women more vulnerable.

She said women also became more reluctant to report violence and abuse to police because of police harassment and the women not being taken seriously.

Hamilton recalled she had set up a safe place, Grandma’s House, for sex trade workers in the downtown eastside.

She said police shut down Grandma’s House, despite former Vancouver police chief Terry Blythe saying he was supportive of Grandma’s House.

“If they were supportive, they wouldn’t have shut us down while a serial killer was roaming the streets,” Hamilton told the inquiry.

A number of years ago, a feminist scholar compared women who are paid to have sex and men who are paid to play sports. She noted the ressemblances: physical talents, skills, and risks are involved for both. Yet one activity is celebrated, the other scorned.

There are a multitude of factors that bring sex workers and clients together, in the quest for gratification, for human contact, for pleasure, for validation and for transcendence.

Yes. Transcendence – for sexual intimacy is an ephemeral refuge from suffering.

This disturbs the authoritarians, the fundamentalist religious zealots, those who uphold the law by punishing the messiness of our human yearnings and then, most evidently the disciples of Saint Paul, who loathe the manifestations of human sexuality unless it is justified by the possibility of breeding reproduction.

Decriminalizing prostitution is helpful, if only as a first step toward preventing violence against women who choose – for their own reasons – to work in this realm.

Today’s Ontario Court of Appeal decision will allow sex workers and community workers to set up ‘Grandma’s Houses’ in this province.

Even the ever-reactionary and rightwing conservative Jonathan Kay displays a modicum of compassion, in his attempt to deconstruct the ruling, though he could have left his condescending, judgemental last paragraph out.

In order for healing to occur, a safe place is required. Persecuting women who embody our phobias about human sexuality has to stop. Hopefully the time has come to rationally address these significant questions, instead of mucking about in the minutiae of fundamentalist religious and ideologically-based morality.