Thomas Mulcair: Man of Principle Mr. Mulcair was asked a simple question, loaded with peril, and he answered it very clearly in the last debate on foreign affairs. His answer to the question whether he agreed with the federal court’s decision regarding the right of a woman to cover her

Continue readingTag: 2015 election

CuriosityCat: Poll Tracker: Harper 125 Mulcair + Trudeau 211 = New Government on October 19

Here’s the stark facts of the state of play from today’s CBC/308 Poll Tracker: Note that Harper’s Conservatives are still far short of a majority, the only way that Harper will remain prime minister, given the emphatic rejections by both Mulcair and Trudeau of either opposition party voting confidence in

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Poll Tracker: Harper 125 Mulcair + Trudeau 211 = New Government on October 19

CuriosityCat: Liberal march in BC speeds up – Nanos poll September 29

You can find the latest Nanos poll here. The movement amongst the 66% plus non-Harper supporters towards choosing one opposition party to favour on election day October 19 is speeding up.In BC the Liberals have moved up sharply, at the expense of the N…

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Liberal march in BC speeds up – Nanos poll September 29

You can find the latest Nanos poll here. The movement amongst the 66% plus non-Harper supporters towards choosing one opposition party to favour on election day October 19 is speeding up. In BC the Liberals have moved up sharply, at the expense of the NDP: And in Battleground Ontario, with

Continue readingCuriosityCat: The Debates: Who won, who lost, and why

|

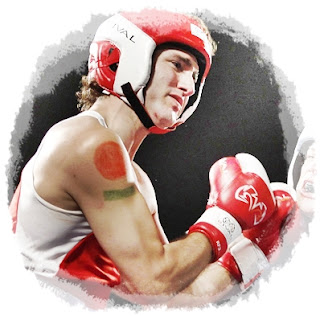

| Trudeau: The Fighter |

Let’s start with the view of how Tom Mulcair behaved in the Munk foreign policy debate, from Gerald Caplan:

But if I remove my mask of detachment, I must report that it was not at all the night the NDP needed to recover its faded lead. But there’s still three weeks left – a lifetime in politics. We have the most polarizing and, yes, dangerous, government in Canadian history and we have the NDP positioned to take advantage of it. Yet the NDP focuses its attacks far more on Mr. Trudeau and gives the government almost a free pass. A huge mistake, in my view. And not too late to change, by any means. It ain’t over till it’s over, in baseball or politics.

Each of his debates have proved disappointing, when they were supposed to seal his deal with the electorate. I fear the deal is almost becoming null and void.

This time, there was political blood in it.

Then, close on his heels, came Mulcair.

And Trudeau? Most thought it would be a victory for him if he did not fall flat on his face while walking to the podium; once there, if he did not collapse like a squeaky and ill-tied birthday balloon; and during the one-on-one segments, if he could snatch a small portion of the air time away from the two debatemeisters.

Trudeau has the luck of being underestimated, like Jean Chrétien was, and the intelligence to turn to experienced people the way Pierre Trudeau and Lester B. Pearson did. Perhaps like all Liberals, there is the will to win in his blood. Given his family pedigree, perhaps the will to win is not only powerful but predestined. Yet if he achieves victory, it will not be just because of his last name, but because he works hard, performs well, knows his weaknesses, and plays to his strengths.

Speaking to the Globe and Mail’s editorial board on Wednesday, Mr. Mulroney said he believes Mr. Trudeau is a strong candidate who shouldn’t be underestimated. “He’s a fine young man, he’s going to do well,” he said. “And I’ll tell you: People who underestimate him, they do so at their own peril.”

He said he considered Mr. Trudeau’s father to be a “very tough, able man,” adding, “You know, the apple sometimes doesn’t fall far from the tree. He certainly has some of the grit of his dad, and he’s obviously got, as well, he obviously has some of the qualities required to win an election.”

“Let’s be very clear. My fists will be up. I am a boxer,” he said.

CuriosityCat: The Debates: Who won, who lost, and why

Trudeau: The Fighter Let’s start with the view of how Tom Mulcair behaved in the Munk foreign policy debate, from Gerald Caplan: But if I remove my mask of detachment, I must report that it was not at all the night the NDP needed to recover its faded lead. But

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Is an anti-Orange Wave rising in Quebec?

As the 1980s gave way to the 1990s and the defeats kept coming, I became ever more convinced that there were crucial bits of a governing coalition missing for Labour. Where was our business support? Where were our links into the self-employed? Above all, where were the aspirant people, the ones doing well but who wanted to do better; the ones at the bottom who had dreams of the top? … Where were those people in our ranks? Nowhere, I concluded…But it seemed that the party and the voters were in two different places, and so the party had to shift against its will. My own feeling, however, was: the voters are right and we should change not because we have to, but because we want to. It may sound a subtle difference, but it is fundamental.

Clause IV was hallowed text repeated on every occasion by those on the left who wanted no truck with compromise or the fact that modern thinking had left its words intellectually redundant and politically calamitous. Among other things, it called for “the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange.” … At a certain level, it meant a lot and the meaning was bad. Changing it was not a superficial thing; it implied a significant, deep and lasting change in the way the party thought, worked and would govern.

I always remember him saying, “Don’t forget: communication is fifty per cent of the battle in the information age. Say it once, say it twice and keep on saying it, and when you’ve finished, you’ll know you’ve still not said it enough.”

The pathfinder was already switched on: growth was the key; investment, not tax cuts; redistribute, but carefully and not touching income tax; keep the middle class onside, but where growth and redistribution allowed, focus on the poorest; then, in time, you could balance tax cuts and spending.

CuriosityCat: Is an anti-Orange Wave rising in Quebec?

Abacus has a poll out on September 27 that has very bad news for Mulcair’s NDP. The NDP support in Quebec, its heartland, has plunged over the past week, dropping like a stone, while the other parties are ticking upwards: And this anti-Orange Wave has dragged the NDP down nationally

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Will Mulcair look left and Harper’s eyebrows not move in Monday’s debate?

An expert in body language viewed the French language debate and Christine Gagnon had this to say about Tom (Thomas?) Mulcair’s body gestures: Watch for Mulcair to repeat these gestures in Monday’s debate on foreign affairs. What about Harper? The expert says he had a fake smile, and his eyebrows

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Has Harper given up his “right not to resign”?

“I will resign …” It seems that the Governor General has gone on record as saying that the “basic principles” of Canadian constitutional law and conventions starts with a simple one: a sitting prime minister has a “right not to resign”: Johnston, a constitutional expert himself, advised then Ontario Lieutenant

Continue readingCuriosityCat: If the “hole” in the Liberal 4-year Plan is not $6.5 billion, then explain how big it is

The presentation of the Liberal plan leaves something to be desired, with the Conservatives blethering about a $6.5 billion hole that will be filled with tax increases on the middle class and on seniors, and the NDP just going on about everything in general. Here’s one explanation in Macleans of

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Quick summary of the Liberal 4-year Plan

So what is in the Liberal spending plan? You can find the plan itself at this site. The plan is well-written, with a clear explanation of the principles that underlie it, a good layout of the major expenditure and revenue items, and a comparison of the different governance values that

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Liberal Party edges ahead of NDP in seats

Poll Tracker, that nifty combo-projections by the CBC and 308, for the first time today shows the Liberal Party nudging ahead of the NDP in number of seats it might win. Here’s the graph: Liberal Party overtakes NDP in seat count Notice, too, that according to Nanos Trudeau has pulled

Continue readingCuriosityCat: The Biggest Wedge Issue in the 2015 Canadian election campaign

When Canadians reflect on the success of the Liberal Party in gaining power in the October 19 election, many will not know how important one issue was in gaining that victory. Nor will many Canadians know who was the mastermind behind that winning issue. Thanks to one of the masterful

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Strategic voting taking root in Canada 3 weeks before election day

Dead cat on a table strategy Some 3,000 Canadians have crowdfunded polls by Leadnow of 31 crucial ridings across Canada where the margin of victory of the Conservatives was small enough to be vulnerable to strategic voting. You can read about it and access each riding’s results here. What seems

Continue readingCuriosityCat: The Politics of Fear lifting the wallowing Tory ship?

After weeks of polls showing a virtual three-way tied between the Conservatives, NDP and Liberals, along comes one poll that shows these startling upticks in Conservative support: The poll results now show the Conservatives with clear leads in British Columbia, Alberta, the Prairie provinces and in Ontario, where 38.7 per

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Harper fatigue in Harperland

“In the name of God, go!” Twice, in British history, have words been uttered to a leader that his time is up: once, in Cromwell’s time, and again, in 1940: In the spring of 1940 British forces in Norway were overwhelmed by the Nazis. On May 7 Prime Minister Neville

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Tom Mulcair says Not a Snowball’s Chance in Hell he will prop up a Harper minority government

The end of the Harper era Tom Mulcair has firmly rejected any chance that the NDP would support Stephen Harper’s government in any confidence votes after the October 19 election: Earlier Wednesday, Mulcair was also asked whether he would support a Conservative minority government. “There isn’t a snowball’s chance in

Continue readingCuriosityCat: Latest changes since September 15 in this fascinating article

You cannot take your eyes off the poll results with the race in the 2015 Canadian election so close! Here’s the graph for the change since September 15: And here’s a quick summary of where the action is (my underlining): Only 11 seats separate the three main political parties, according

Continue reading