Yesterday’s third quarter report from the Ministry of Finance indicates that their estimate of the deficit for 2016/17 fiscal year has fallen by $2.4 billion — from $4.3 billion to $1.9 billion. This despite the announcement of another $223 million in new spending increases for 2016/17. If you recall, the

Continue readingAuthor: Doug Allan

Defend Public Healthcare: Ontario government spending grows. But the deficit falls like a stone

Yesterday’s third quarter report from the Ministry of Finance indicates that their estimate of the deficit for 2016/17 fiscal year has fallen by $2.4 billion — from $4.3 billion to $1.9 billion. This despite the announcement of another $223 million in new spending increases for 2016/17. If you recall, the

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: The end of provincial public sector austerity in Ontario?

The experts appointed to review the claim by the Auditor General that the surpluses in the teacher and civil servant pension plans cannot be counted as government assets have reported. Importantly they have sided withthe government and against the Auditor General, Bonnie Lysyk. Lysyk’s pension surplus accounting policy required the

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: The end of provincial public sector austerity in Ontario?

The experts appointed by the Wynne government to review the recent claim by the Auditor General that the surpluses in the teacher and civil servant pension (Read more…) cannot be counted as an asset to reduce the provincial government’s debt and deficit have reported. Importantly they have sided withthe government

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Do economies of scale explain low hospital funding in Ontario?

Funding for hospital services in 2015/16 was 25% more in the rest of Canada than in Ontario. Some have tried to downplay this, arguing that economies of scale should allow Ontario to provide hospital care more cheaply. Notably, however, the World Health Organization dismisses the notionthat economies of scale are

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Ontario deficit cut over $5 billion in one year as revenue rolls in — but who will benefit?

The government’s unaudited financial statements for 2015-16 have been released (in lieu of the Public Accounts) and the deficit is down another$700 million from the last government estimate. Combined with earlier reductions, that means they came in with a deficit $3.5 billion less than they originally budgeted for 2015-16 in

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Health care funding falls far short even as Ontario heads out of deficit

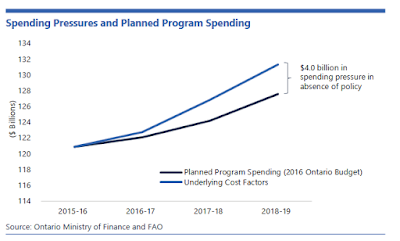

A new report from the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) confirms the difficulties government cuts are placing on public health care in Ontario.

The FAO is a government-funded but somewhat independent office that reviews Ontario government economic and fiscal claims. This is not a left wing think tank — rather it is very much part of the received establishment.

Its latest report notes that government spending plans will fall $4 billion short of what is required to maintain services at 2015/16 levels by 2018/19:

Moreover:

The biggest funding gap is in health care.

Health care is facing 5.2% cost pressures the FAO notes: 2.2% due to population growth and aging and 3% due to growing wealth and inflation.

“Assuming that the quality and type of health care services provided in 2015 remains the same over the outlook, the FAO estimates that population growth and aging would contribute 2.2 percentage points per year on average to the growth in health spending. A stronger economy, which leads to higher incomes and price inflation would contribute a further 3.0 percentage points. Combined, these factors would lead to 5.2 per cent annual growth in health spending.”

The FAO notes the government plans health care funding increases of 1.8% over the next four years.

Accordingly it concludes:“Given these factors, it is unclear how the government will achieve its target of 1.8 per cent annual spending increases (for health) over the next four years.” (My emphasis.-DA)

While in the past, our health care system was getting “enrichments” — it is now getting significant “efficiencies”.

Ontario’s Economic and Fiscal Situation: The news from the FAO is a little better than it has been in the past.

According to the FAO, the economy is improving, revenue is growing (albeit not quite so quickly as the government hopes), and spending pressures are building. As a result, the government (absent new policies) will briefly achieve little or no deficit in 2017-18, but then return to deficit. The key debt to GDP ratio however has stopped getting worse and is beginning to modestly improve.

The take-away? For what it is worth, this representative of mainstream opinion believes we are more or less on track for a balanced budget in 2017/18, that government funding for public programs is falling behind real cost pressures, that health care is being hit hardest of all, that it is unclear how government can achieve such low level funding increases for health care, that funding for public programs and especially health care will have to increase in the medium term, and that, absent new policies, we will go back into modest deficit after 2017/18.

Defend Public Healthcare: Financial Accountability Office finds health care funding is falling short

A new report from the Financial Accountability Office (FAO) confirms the difficulties government cuts are placing on public health care in Ontario. The FAO is a government-funded but somewhat independent office that reviews Ontario governmen…

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Cuts drive crisis for unpaid women caregivers

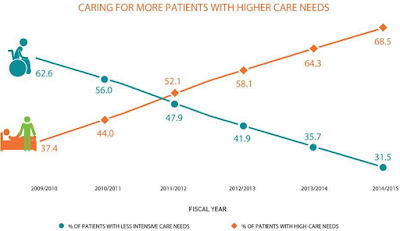

With hospital cutbacks and a virtual freeze on long-term care beds, home care and unpaid caregivers must now take care of sicker and sicker patients. This change in home care has been sudden and dramatic, as demonstrated in the graph below from the the Ontario Association of Community Care Access Centres (the OACCAC represents the public sector organizations which manage home care for the government).

The OACCAC estimates cost pressures of about 5% per year to offset demographic changes and for the absorption of patients that would otherwise have been treated in hospitals or long-term care. The OACCAC adds that funding has fallen short of that level in recent years, reducing care.

- Among patients with moderately severe to very severe impairment in cognitive abilities, 54.5% had caregivers who were distressed.

- When patients needed extensive assistance with or were dependent in some activities of daily living, 48.7% had distressed caregivers.

- When patients were at the two most severe levels of health instability, 56.1% had caregivers who were distressed.

- Those who had Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia increased to 28.6% from 19.5%

- Those with mild to very severe cognitive impairment increased to 62.2% from 38.1%

- Those experiencing moderate to very severe impairment in ability to perform activities of daily living such as washing their face or eating increased to 44.5% from 27.6%

- Those with slightly to highly unstable health conditions associated with greater risk of hospitalization or death increased to 43.2% from 27.3%

- The patients averaged a year and a half older than in 2009/10, increasing from 77.4 years to 78.9 years.

- On average, patients whose caregivers experienced distress received 31.5 hours per week of care from those caregivers, compared to the 17.1 hours per week received by patients whose caregivers were not distressed.

The home care patients are much sicker than they were only a few years ago, increasing the burden for the unpaid caregivers. The result for the unpaid caregivers — usually women — is increasing distress, anger and depression, with a significant portion unable to continue. More paid hours for PSWs and other home care workers is obviously part of the solution.

The study — released by the government sponsored organization Health Quality Ontario — does not specifically connect this “perfect storm” to the ongoing health care cuts. But it is clear those cuts are driving sicker patients to home care and unpaid caregivers — and now we know those women caregivers are basically being thrown under the bus.

The main government response to the cuts in hospital and long-term care is to suggest that they are doing more in home and community care. This study suggests this response has big problems.

Update May 16, 2017: A new study published by the New England Journal of Medicine and funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Ontario Academic Health Science Centre, the Ministry of Health, and the University of Toronto also shows major problems for caregivers. Specifically, in this case, very high levels of depression among caregivers (who were mostly women) of patients who survived a critical illness.

Defend Public Healthcare: Cuts drive crisis for unpaid women caregivers

Cascading health care cuts are resulting in significant problems for home care patients and their families, seriously undermining the main defense the government makes for its policy of hospital and long-term care cutbacks. With hospital cutbacks …

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Ontario to cut funding for hospital infrastructure in half. Austerity bites

The Ontario government recently put out a release bragging that they will fund $50 million per year to renew existing hospital facilities. However, in her September report the Auditor General reported that Ontario hospital funding is les…

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Ontario to cut funding for hospital infrastructure in half. Austerity bites

The Ontario government recently put out a release bragging that they will fund $50 million per year to renew existing hospital facilities. However, in her September report the Auditor General reported that Ontario hospital funding is les…

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Ontario hospital length of stay in rapid decline, Canadian average now 21% longer

New hospital inpatient length of stay data published by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) indicates [1] Ontario lengths of stay continue to decline, but the pace of decline has picked up, and [2] the gap between the Ontario and Canad…

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Ontario loses 19,000 public sector workers while rest of Canada gains 73,000

There has been a general trend downwards in public sector employment in Ontario according to Statistics Canada. In the last two years, Ontario has lost 19,000 public sector workers, with most of the loss occurring in the last year.The downwards trend i…

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Health Care and the Budget: Not Much

Health care and hospital funding: Despite significant new revenue and lower than expected debt costs, health care spending is almost exactly identical to the amounts planned in last year’s Budget for 2015-2018. The total health budget for 2015/1…

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Health care declining as share of economy and program spending

Federal Health Cash Transfers to the Ontario government will rise 5.94% in 2016/17, or by $778 million. This, in itself should amount to a 1.5% increase in Ontario even without a single extra penny from Ontario tax revenues. This will follow…

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: 37 health care findings by the Auditor General: Performance Problems

The litany of health care problems identified by the Auditor General is frightening. Here’s thirty-seven of them.Local Health Integration Networks (LHINs): Problems, Problems, ProblemsLHINs have not met performance expectations. “Most LHINs performed …

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Revenue up $1.2 B: Ontario overestimates deficit — for the sixth year

The Ontario government is forecasting that it will beat the deficit forecast for the sixth year in a row according to the province’s Fall Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review.The deficit for this year is forecast to be $1 billion less than forecast …

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: Canadian hospital funding now 25% more than Ontario funding

Provincial government per capita expenditures on hospitals continue to decline. This is the third year of absolute decline according to Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) data.Of course hospital services are also affected by inflation, like other services. One way to measure this, perhaps, is the total health care price

Continue readingDefend Public Healthcare: The long series of failures of private clinics in Ontario

For years CUPE has been concerned the Ontario government would transfer public hospital surgeries, procedures and diagnostic tests to private clinics. CUPE began campaigning in earnest against this possibility in the spring of 2007 with a tour of the province by former British Health Secretary, Frank Dobson, who talked about

Continue reading